Can we afford to be avant-garde?

What is it like to create an offshoot project, based on proprietary software? Is there space for it in Poland? These and other questions are answered in a conversation with Natalia Podyma [NP] by Cloud Theater director and founder Teo Dumski Chomiak [TD].

Imagine entering an empty theatre space, or even moving the theatre into a cinema space. It's dark. And suddenly everything is being built before our eyes in one creative act. From the music to the set design to the actors. Teo Dumski Chomiak - director, actor, educator at the Wroclaw branch of AST. As an experimentalist, looking for new means of expression, wanting to combine technology with creative use in theatre, he created Cloud Theater (Theater in the Cloud). The first theatrical creation in Poland using, technology and author's software allowing to transfer the audience to another dimension of participation in art.

[NP] Let's start from the beginning - where did the idea to create such an activity come from?

[TD] I've always felt a rift within myself - between technology and artistic interests. My father is a physicist, so since I was a kid I was inspired and pushed towards science. Even as a kid, I was interested in computers and took my first steps in programming. At some point, artistic desires took over. Having already got a place at the Polytechnic, I had the idea of applying to drama school. I got into AST in Wrocław and graduated. Then I looked for my place in the art offered by various theatres, but I noticed that technology had no place in them. It was rarely used at all, and if it was, it was only to facilitate something for the creators: changing lights, scenery, etc. I saw technology as a separate means of expression.

[NP] What was the next step?

[TD] Inspired by Larry Gonick's 'History of the World in Pictures' comic book and Witkacy's Art Theory, which I've been a fan of ever since I met it, I thought it would be great to do a show that told the whole story of the world. I wanted to tell everything, as Witkacy wrote, "in one flash" - to escape the linearity of the story and see everything in one flash.

[NP] Well, exactly how do you tell the story of the world? Mix in bits and pieces from the jungle or the age of the dinosaurs, and then, for example, move into a war climate?

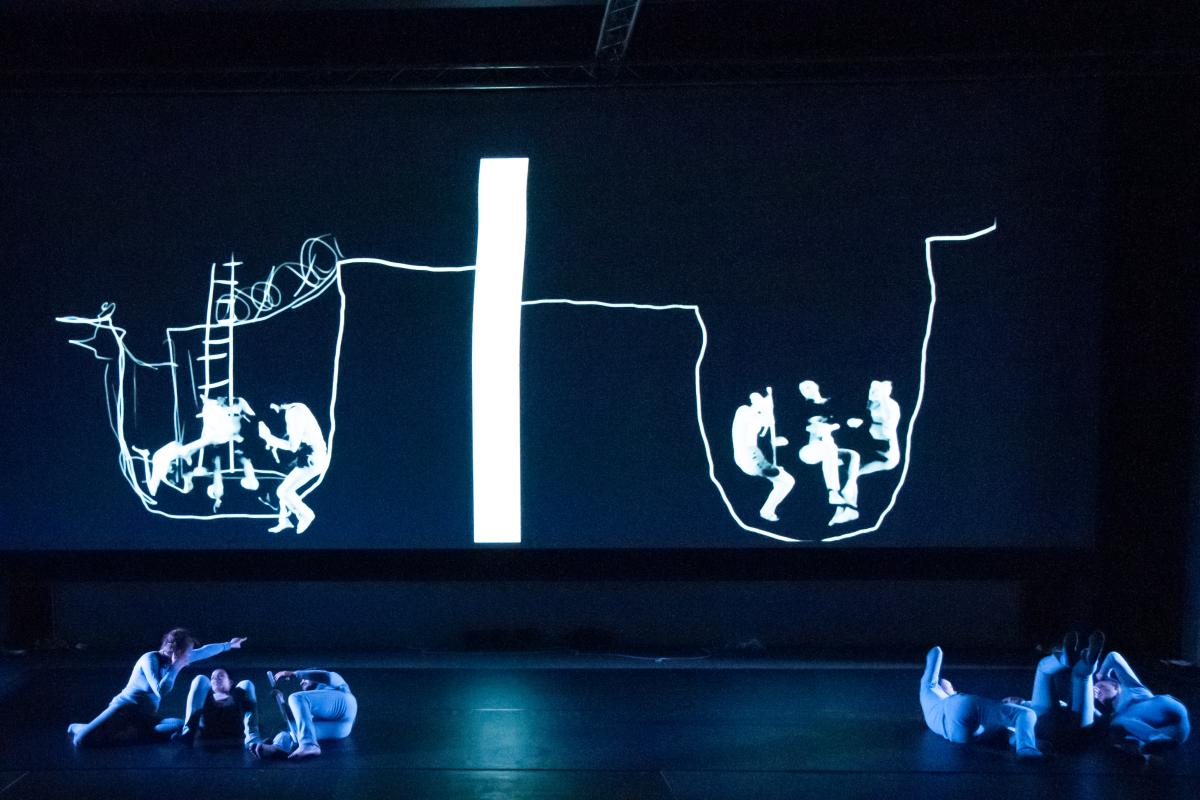

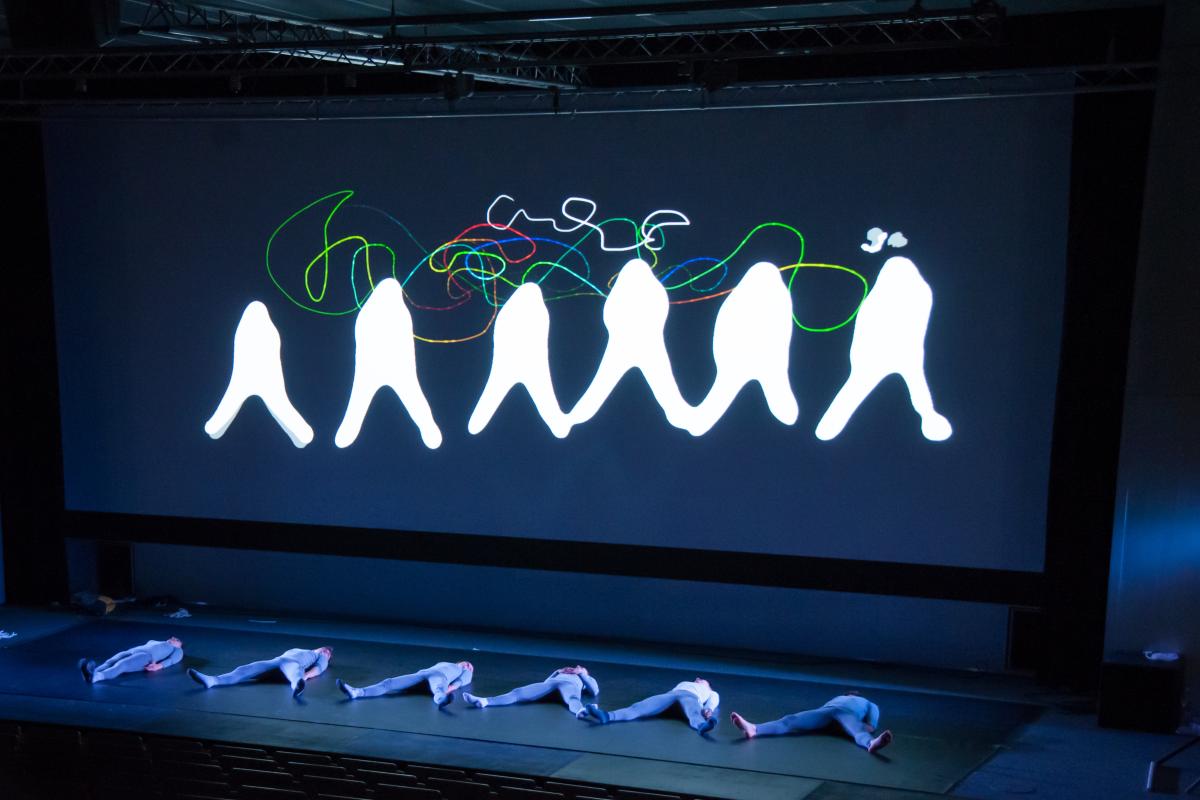

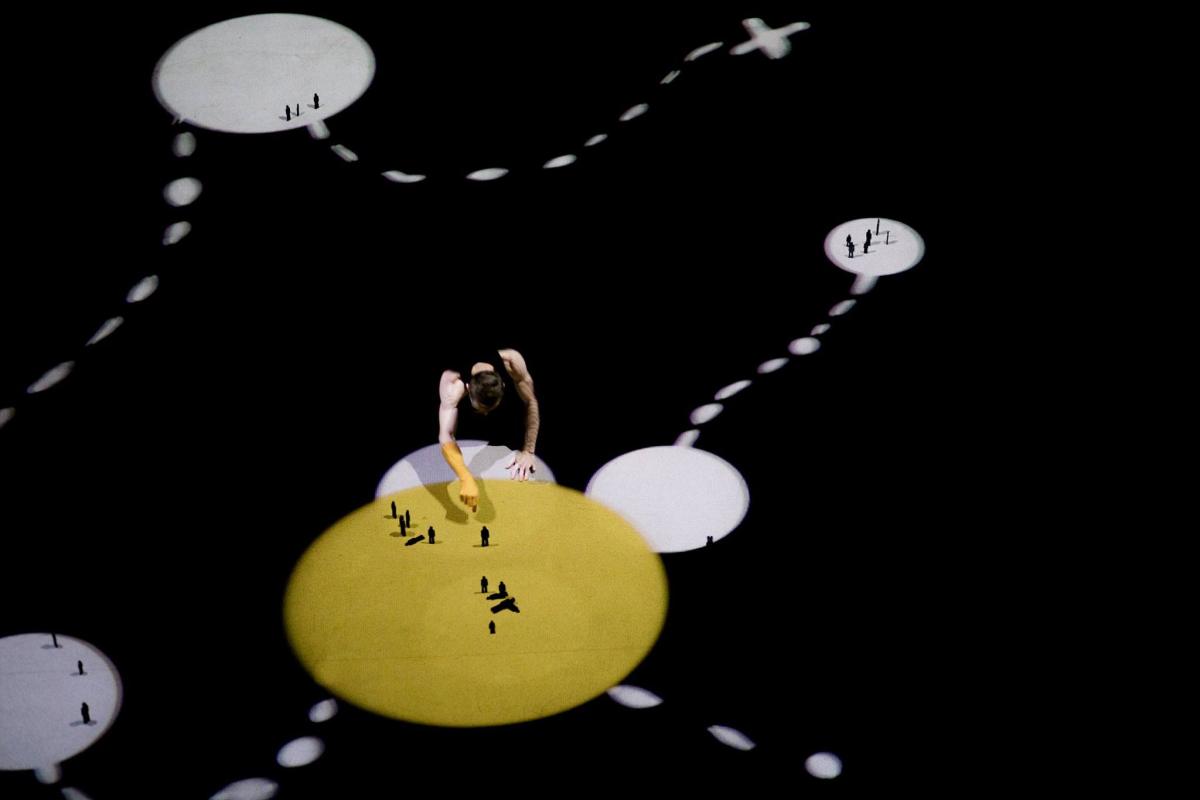

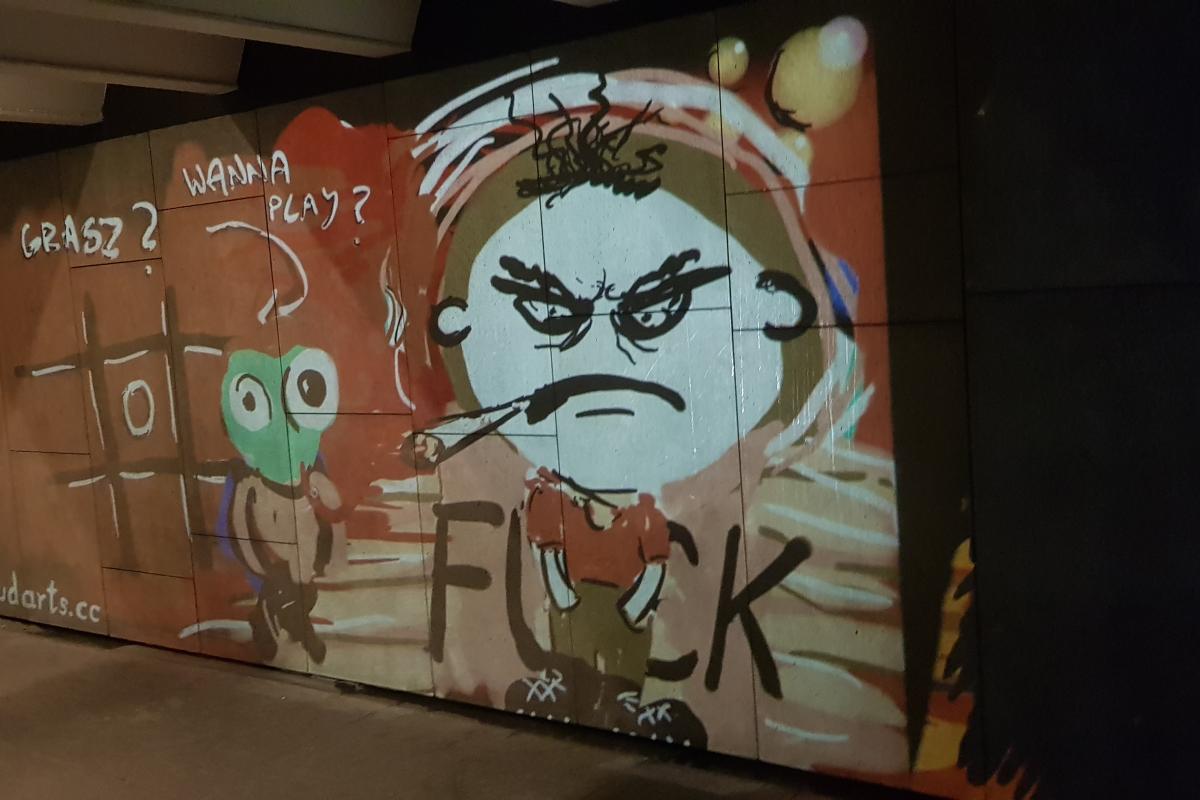

[TD] I knew that if I wanted to do it 'classically' I would need a huge budget for set design, which I didn't have. So I started experimenting and looking for new tools, I felt that with the means available it couldn't be done. At the time, I was working at the Ad Spectatores theatre in Wrocław on a technique we called 'floor acting' (Maciej Masztalski once gave me inspiration for this and that's how it started). What I mean by 'relief' playing is that the camera is on top, the person is lying on the ground and the image is projected on the horizon of the stage. I realised that it was this means of expression that allowed me to tell many more things than when an actor is standing normally on stage. If only because it was possible to break free from gravity. It was possible to create images with a human being in the lead role but still defying physical principles. And then I thought - what if I were to draw this scenery? Quickly sweeping, just outlining the action locations and situations? I mean, what if you took an image of this actor lying on stage and somehow digitally integrated it into the set design? Graphic tablets proved to be the starting point. Of course, there was no software on the market that allowed you to draw live and compose that with a video image. However, the skills I had acquired since I was a child allowed me to create such software. I started a collaboration with one of Wrocław's institutional theatres. The theatre director agreed to invest in making this project happen. We were given a space and some full-time actors who agreed to participate in this side project. Over the summer holidays, together with the actors, Adam Kabat - a cartoonist whom I invited to collaborate - an IT specialist - that is me - we created a play together entitled. A Brief Outline of Everything'. We even had a premiere at the New Horizons cinema! The idea of bringing cinema to theatre is quite well-known, but bringing theatre to cinema - that's something else. Unfortunately, however, this theatre withdrew from co-producing this show just a few weeks before the premiere. It was a total disaster for me. We had a show that was basically ready. All we had to do was polish it. I was left alone with nothing - only a contract for the premiere and no team.

[NP] But it worked out in the end?

[TD] Yes, there were two people around me - my brother and Patrycja Obara - who convinced me that putting everything up in 4 weeks could work (including, of course, the time to find five actors and try to recreate the action). Thanks to their support and financial help, it worked! On 7 February 2016, we premiered the play 'A Brief Outline of Everything'. With new material, a director little known in the city, a new ensemble, a completely innovative idea - we managed to fill a 350-seat auditorium! And that's where it all started. We thought it was a good time to inaugurate the existence of a new theatre company. We called ourselves Cloud Theater! And although we sometimes joked that it was "crazy cloud theatre" in fact, behind the name was the innovative idea of "working in the cloud".

NP] What other later initiatives were there?

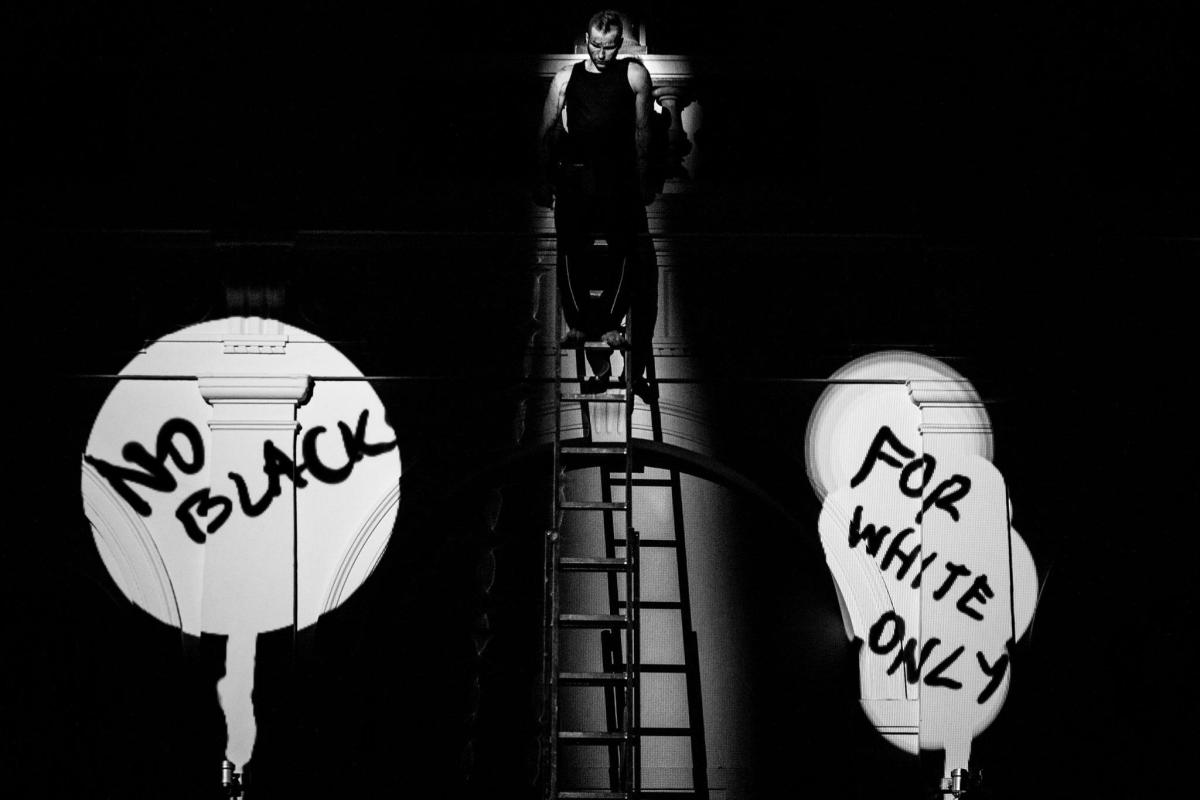

[TD] With our first production, a play called 'A Brief Outline of Everything', we got into a dozen notable festivals. We travelled around Europe - we were in Belarus, Budapest, Cologne. We were even the first ever independent theatre to appear at the Divine Comedy Festival in Krakow, for which I am still grateful to Bartosz Szydłowski, who decided on such a crazy idea and invited us.

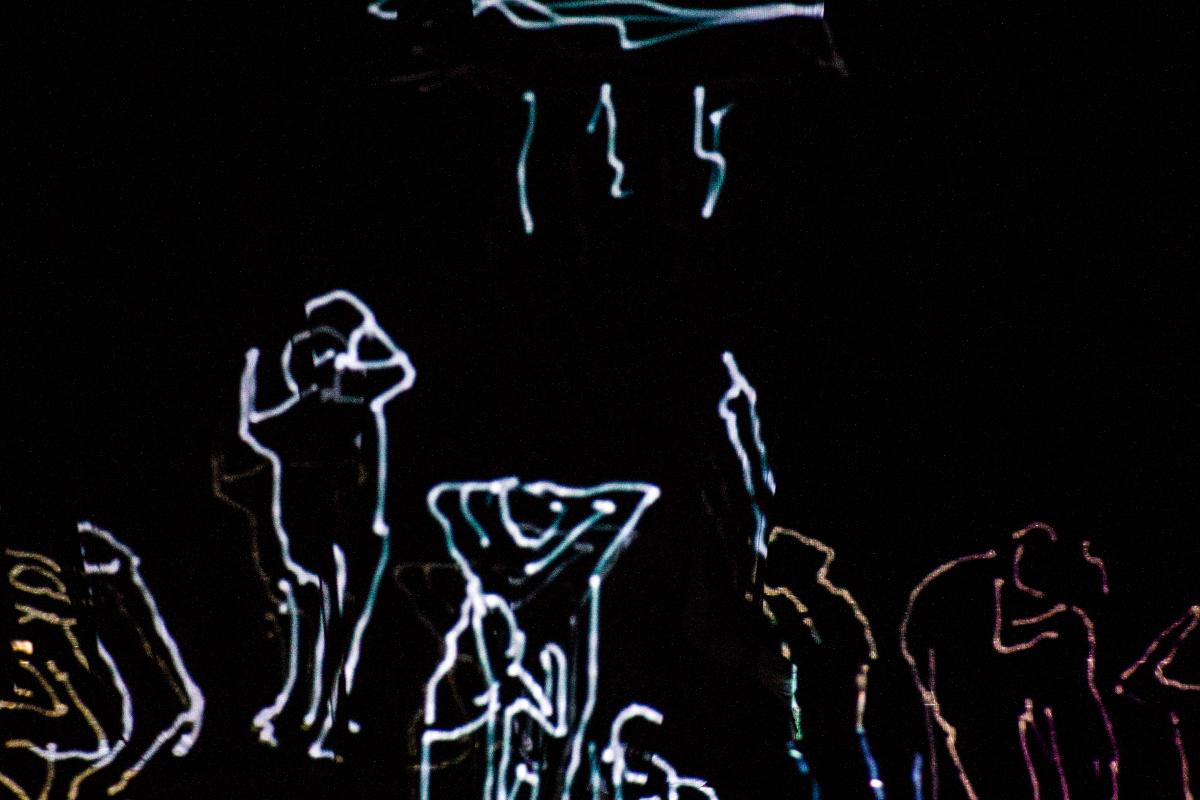

Then the idea arose to create a sequel to this story, focusing this time on fantasies related to the future. This is how we came up with the performance 'Technology is a Being', which premiered at the Centre for Audiovisual Technologies in Wrocław. In this performance, we 'got up off the floor'. We started to draw scenery in 3D space. We continued to develop our live drawing tool but already in the 3D space of the stage. Even towards the end of the performance, the actress, Maryla appeared on stage with a 3D printer I had constructed myself. Perhaps this was the first time in the world that a 3D printer appeared in a theatrical production. It was a kind of punch line to the story of mankind's fantasies and machines that last longer than humans.

Trailer spektaklu - "Technologia jest istotą" - reż. Teo Dumski - Chomiak

NP] The new production sounds very innovative and fresh. Has there been any awards?

[TD] I received the "WARTO" award given by Gazeta Wyborcza and funded by the City of Wrocław, for "a successful marriage of technology and theatre". In fact, the story of my disappointments began with this award. I had hoped that this award - just like films about some great artists - would open the gates behind which would be: audiences, money, careers, popularity and the chance to finally not work for free and to be able to fulfil my dreams while giving something interesting to the audience. However, this did not happen. Just as the premiere of a new show was quite successful, the second and third shows after the premiere were a flop. The performances were attended by 15-20 people each. Even then the slow decline began, despite visits to many important festivals. We were also invited to conferences on new media and technology in theatre or film as speakers and presenters.

[NP] What was the feedback from audiences that the arts were catching in the business space?

[TD] This was the case, for example, at the 2017 edition of TEDx Wrocław at the Capitol Theatre. At the time, Michal Kasprzyk invited me to create a TEDx Talk. However, I thought to myself that talking about the technology was a mistake, it's difficult to talk about things that the audience can't imagine. I encountered this often. There have been audiences who have listened to our technology, looked at pictures and recordings and then come to the performances and share with me the reflection that they imagined it completely differently. Therefore, I decided to use my 20 minutes by creating a short performance on stage and show it as a TEDx talk.

This was received very enthusiastically, although at many other conferences I was perceived as an absolute freak and, despite the variety of the conference programme, I often became almost a circus attraction - people took out their mobile phones and took pictures instead of listening to us.

[NP] Let's go back to the technology you used at Cloud Theater. A key element in the operation of the Cloud Theater was the software. As I understand it, you are the author of this system? There is no other like it in the world?

[TD] Yes, it is software that creates completely new possibilities. I even tried to contact the large corporations that make graphics tablets and distribute them to the world market to ask - if they could help me develop this unique idea. Each time, however, I got a very quick and simple answer: no. They couldn't imagine what the purpose of this would be - you had to write your own drivers for the tablets because they weren't suitable for this kind of use. Had I not had the IT skills, the creation of this software would have been impossible. The software has been developed exclusively by me to this day.

[NP] Do you make different software for each show?

[TD] Not completely, but each time we add new features. To be honest, mainly because with each production I would like to have more possibilities and resources - for example, new colour palettes, new drawing possibilities, new effects. We didn't buy software to get these effects, we simply rewrote the software almost during production and perfected it. Today, I can see a big difference, for example, in the line (which the algorithm created) between the first and the last production.

[NP] In the age of VR, we also have the possibility to draw in space all sorts of things seen through the goggles. What then makes Cloud Theater different? The drawing of scenery in real time? Is that aspect the most valuable?

[TD] Yes, in general it's probably the most key thing, which I've been very much defending from the very beginning. I believe that new technologies only have a chance to exist in theatre if their construction does not displace the element of unpredictability and the human element from the stage. That is, if we draw - let's draw live, if we play music with a synthesiser - let's create it here and now, if we project images - let's generate them live, if we project a film - let's shoot or at least edit it in front of the audience. Whenever we use technology, in order to automate something - it stops being theatrical.

[NP] In a world constantly striving for constant automation, it's hard to maintain your ideals. Probably many people have suggested other, faster solutions to you. However, drawing in real time also has a different effect, doesn't it? You can't talk about reproduction here...

[TD] How many times has someone suggested to me that "after all, it can be recorded and then played back" or "let's just draw a few details live and play back the rest from the recording, no one will catch on"? Right, but that's only how we did music videos or animated films because this art form is all about playback. Such advice sometimes drove me crazy. However, I have always tried to explain that, for me, such automation completely kills the theatricality of the event. I prefer to dispense with some of the scenery in favour of the creative act arising truly live. Every line, every pixel is alive, like issues spoken by an actor.

The technology then becomes an actor who collaborates with us in creating something alive, rather than being an automaton that does something for us.

The essence of technological theatre is that without a human being at the tablet, on stage, on camera using the technology - absolutely nothing would be created. It would be empty and black, nothing. How we use technology I sometimes even see it as a domination game of Masters and Slaves (hence, of course, the fear must be born that the Slave will one day 'repay' the Master, sound familiar?). My idea was to give Technology the right to live and work with it, not just use it. Today, in the age of the popularity of Chat GPT this may cause an even bigger stir than it did then.

[NP] What other feedback was there from audiences seeing such a performance? Did they appreciate the essence of the live process?

[TD] Definitely! From the beginning I gave a lot of exposure to the people who are normally behind the scenes and responsible for the whole performance. I brought everyone out - the editor who edits live, the musician-multi-instrumentalist, the illustrators who draw the set design in front of the audience's eyes, as well as the technicians behind the screens and all the controllers for picking colours and brushes. So our performances were not just the result of all these technological installations but also a performative part revealing the creative process itself and the whole construction. Sometimes some audience members preferred, instead of looking at the stage, to approach the illustrator and watch him do it. A really big part of the audience didn't believe us. It was as if they were used to the fact that there was always a cheat. That always hit me hard - the sincerity of us artists in terms of our use of resources was usually questioned by someone. As if we were suspected of this half-playback. There was always someone in those backstage conversations who said: "Well, but wait, really? After all, this computer can play a thousand of these images at once, and you're drawing one! Surely you're making something easier for yourself'.

Perhaps in a culture where we have so much automatic, beautiful, moving images and sounds (not to mention AI generating them), we are not only used to it, but we don't even see the point in creating the here and now and being real. Once, in one review, someone called our theatre 'poor theatre' I think this is a very insightful and apt term.

Our theatre, even though it is saturated with technology, is still poor because it exposes not only man, who without technology is unable to create anything here, but also technology, which without man is unable to function.

Theatre is about itself, about Man and his Technology, about process, about truth, about creativity - that's what has always fascinated me the most.

[NP] It is said that the highest price is paid for truth. What costs do you incur for not taking shortcuts? What is the financial difference between automated solutions and the very artisanal work of each implementation?

[TD] This aspect is very difficult. If I said how much these performances cost you would probably say it's not much. On the other hand, if I priced the work of creating the programming on the market it would already go into the thick hundreds of thousands and even the big theatres would say: "Wow! that's quite a budget already!".

I was able to produce these shows because I was able to combine skills from many disciplines, I dedicated 100% of my time to it and the help of several people who personally cared. We funded most of the production ourselves. Subsidies from private sources or the Department of Culture only allowed us to briefly quell frustration or make sandwiches for rehearsal.

[NP] There were, however, institutions that invited you to collaborate?

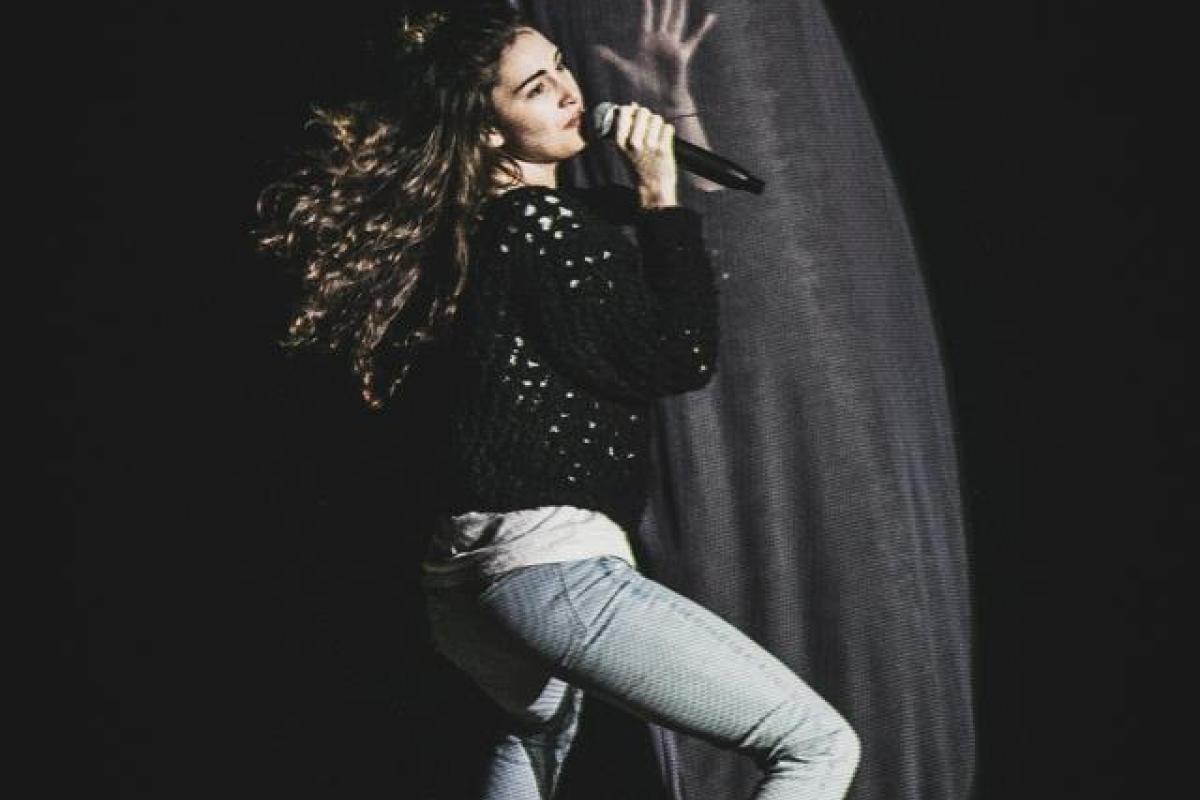

[TD] Yes, we still created a big performance "Don K." in co-production with the Wrocław National Museum (also financially), thus measuring ourselves against the legend of Tadeusz Kościuszko. At first I was very reluctant about the idea, I didn't want a laurel to the national hero. Forced by myself to look for something new, I created a drawing script - which was the basis for a trans-language performance without words. We did a simple kind of projection mapping, obviously drawn live by Sebastian Siepietowski (a cartoonist who started working with us right after Adam Kabat). The realisation really went well and we played this performance many times. However, with the departure of the person who liked the museum's flirtation with theatre from his job at the National Museum, we stopped playing there. Looking for other opportunities we turned to musical production. Patrycja Obara, who had been with us from the beginning in the role of project manager, changed this role and, while creating her debut album, asked us to create an audiovisual, cartoon set for the premiere concert. At the time, we opted for projection size - we designed not just on the floor, but on all three walls of the stage box. At the Centre for Audiovisual Technology, we created a huge, phenomenal musical event that went far beyond the money it was produced for.

[NP] It must have been a spectacle. The tickets were certainly quite expensive.

It's also very interesting. We produce shows that looked like they cost a quarter of a million and the ticket cost £35. It should cost £200, because that's the natural law of the market, but would the audience then pay for little-known, innovative artists? Or would he prefer to add another 200 zloty and go to see Beyonce in Warsaw? There is some suspicion in the audience that if something costs £35 it cannot be great and of good quality. And at the same time a fear of spending 200 zloty on an avant-garde performance. If we were to produce a new show today then tickets would be very expensive. I would try to do such an experiment to give the audience the feeling that they are paying an adequate price for the ticket in relation to what they are getting. However, I don't think it would be a box office success.

[NP] Let's go back to the financing of the project. Why did you have to look for new opportunities? Where did the problem arise? I understand there was no funding?

[TD] I will say yes, the funding did come in. As I understand it, it was paradoxically the one that started the decline of our theatre. Starting with the repertory business. We started to be financed by the Department of Culture in Wrocław. I hoped that this was the moment when the gates opened and behind them there was audience, popularity and money. However, after just the second year of such funding, it turned out to be exactly the opposite. Particularly as this money was to be used solely for the exploitation of the finished performances. With the annual grant, which we managed to bid for in a public competition, we basically started to shrink our activities. It became more difficult to work on projects, even more underfunded, and harder to get audiences.

[NP] What is the reason for this?

In my opinion, from the fact that there is usually not enough of this money by half. Of course, this goes along with the assumption that 'since you already have half, you only need to get the other half to have all of it' or 'if you don't have money, you don't do birthdays'. I have occasionally heard such things from decision-makers. What we forget is that artists are usually unable to get the second half without promoting themselves first. The first half of the money, on the other hand, is awarded by, for example, the City Council with the proviso that hardly a penny can be spent on promotion. This is a stalemate and a vicious circle. In many competitions there are stipulations that you cannot spend more than 2-5% of the awarded grant on promotion. For this £160, we were able to buy a Facebook post which, with these amounts, was able to get us 10 clicks, with three people coming to the performance. We had to finance most of the promotional activities out of our own pocket, or give free performances on the streets, which was not easy if we had to prepare the premiere at the same time. Maybe if I had worked as an IT specialist (which I thought about very seriously for some time), in a so-called "normal" job, I would have been able to earn good money so that I could spend some of it on theatre. However, for purely practical reasons, I am unable to undertake this - theatre, when done professionally, costs 100% of your time.

[NP] What did you do then after getting the grant from the city? Did you create new plans for new productions or did you play already produced shows? In what years did all this happen?

[TD] It was all happening between 2017 and 2021. We were creating new projects, including musicals, and we were also exploiting finished shows - mainly 'A Brief Outline of Everything' (he was the most 'pop'). There was no more time to go to festivals. In the meantime, Teatr Polski in Wrocław was falling apart and the market was consistently monopolised by the Capitol Theatre, independent theatres were also collapsing, and then... then there was a pandemic. And it worked on us the way the virus itself worked on people. After it hit, those who had previously been reasonably healthy rose up. But those whose health hung in the balance had little chance. This, of course, was also my own deeply considered and hard-won decision. I realised that with such 'poisoned' money it was impossible to continue to function. And the pandemic was just the nail in the coffin. If we were still to do anything, it was only on commission. And such commissions are still happening today! We recently produced an audiovisual set for a play at a theatre in Dresden - Studiobuhne Sachsen - already recorded, of course, but visually characteristic of our style. We also produced, at the Wrocław Puppet Theatre, a set design for the play "How many frogs does the moon weigh?" directed by Agata Kucińska - half drawn live and half automated.

[NP] So have you changed your ideals? Why the sudden use of recordings?

[TD] At its core, Cloud Theater was an innovative collaboration with technology. Other creatives often invite us to fill in only part of their performances, as a visual means of expression. We adapted to their decision, wanting to fill the designated space professionally.

[NP] Is nobility still a value in art today?

[TD] I feel noble when I see other artists inspired by my ideas, but I am frustrated when they don't talk about it. I notice the impact of our innovative means on the theatre market to this day. I am a passionate supporter of attribution culture because we live in a time where creating is very much processing. I know that I am not creating works that flow out of me and only me. I know that I am analysing the outside world and creatively interpreting it, adding my five pixels that make it 'authorial'. But what I encounter in Poland is that most people think that if, for example, you take four techniques and 15 exercises from various theatre workshops you've been to and make your own composition out of it - you can call it 'your method'. Me thinks that, it's a slight deception. You could say, for example, "drawing from such and such methods I created my own composition of exercises". How much truer that is! I think that attribution is very much needed today, because all around us we are full of philosophies like "become a photographer in 24 hours" or "become a business shark in two easy steps". And of course, you can learn the basics of photography in one weekend, but all the rest of these messages are simply frauds. And you can see it in the image of some of the artists that everyone is 'playing to themselves'. Meanwhile, the photographer who takes a picture on the street should be aware that he or she is "only and as much" a creative interpreter of reality in front of the lens. That, in this case, 'authorship' consists of, among other things, his sensibility, his physical work, his decision to press the shutter button, or his choice of lens - but a large part of the artistic value of that photograph is the reality that would look the same if that photographer had not been born (sorry). And the culture of attribution helps us to remember that our work is always a creative transformation of some, usually unconscious, inspiration.As an aside, I once almost burst out laughing at a post-premiere meeting with a director who, when asked "what was her inspiration", hastily replied: "Me, nothing!". For me, it would have been more honest to simply answer "I don't know". Promoting a culture of attribution, after our performances we displayed a 'payroll' which, in addition to the creators, included the names (and first names!) of computers, software libraries, graphics cards, hard drives and 3D printers! And the most interesting thing was to ask the audience what they saw in these performances. Then sometimes it even occurred to me what we were unconsciously inspired by.

These are words that seem a little out of fashion today: nobility, truth, attribution. We are in an age where it is fashionable to operate on the principle of "fake it till you make it" - pretend something is yours for so long until eventually people believe it and then you win.

[NP] What then would have to happen for this Cloud Theater of yours to be reborn like a phoenix from the ashes?

[TD] For me there is an answer in your question. Perhaps it takes a big fire. I don't know, it's not my role to create funding systems. I very much hope that experts in culture and its funding - managers, patrons, officials, having heard this story, could say what needs to change, how to save phenomena like Cloud Theater and not let it fade away.

[NP] I understand, but still, if an opportunity came along and someone would notice you and help you to be reborn, what support do you need at this point? Do you have the willingness?

[TD] The willingness is there of course! Although you know, it's difficult to rise from the ashes. It seems to me that in order to function well I would need a managing director and one zero more money than before (from a grant of 30,000 zloty to 300,000 zloty).This could successfully save the initiative. The vanguard requires not only the courage to experiment, but also the means. I already know from experience that at the same time being an avant-garde artist and managing formal issues, writing dozens of offers in competitions to 'get anything', according to Polish rules and principles - is simply impossible. It's like a thicket for which you need a separate job. It is impossible in Poland today to be an avant-garde artist and an artistic entrepreneur at the same time - it simply cannot be combined.

[NP] Have you thought about changing the place where you operate? To abandon Wrocław and move to another city in Poland or abroad?

[TD] Of course. However, this entails logistical difficulties. Here in Wrocław I live and have a permanent job. I teach acting classes at the Academy of Theatre Arts. To quote Joel Pommerat: "It's such a bare minimum. However, if a situation were to happen where a city takes us under its wing and says: "OK come here for a year and we'll try to rock it together", then I would think very seriously about it. Maybe I would be able, without burning bridges, to resurrect my theatre in another city. The older I get, of course, the harder it is, because it sort of 'grows into life'.

[NP] Can we then afford the avant-garde in Poland? Can we afford the people who produce this avant-garde? Can we afford the audiences who admire this avant-garde? Are we able to trust the avant-garde enough to give it money? Are we able to understand that this avant-garde must sometimes be a failed experiment?

I think the avant-garde can't afford to act on the rules in Poland. We can't lock the avant-garde into indicators, long-term and short-term, bids for performance so that it wins in competitions with something simple, ready-made and safe, and then annex it a few times just to get it right in the papers. I understand that it is what it is and officials are doing what they can because the system is poisoned and badly designed. In my opinion, competitions for grants should look like this: for the first stage you send a description of the idea, e.g. up to 1000 characters. Then hire not civil servants but open-minded theatre experts to read these 1000 characters and select 100-200 interesting projects. I think that really these three sentences are enough to convince this expert that the submitted proposal has potential. It is only in the next phase of the competition that officials should be invited to collaborate, so that they write up the project and price it properly from a business and budgetary point of view. This could save artists from frustration and create a situation in which, by cooperating with the Offices, they receive remuneration adequate to their work. And to enable a vanguard like ours to operate.

If I were to construct a better system, this is how I would start. Then it would have a chance to work - artists could become artists and not retrain as clerks, lawyers and accountants.

[NP] One last question at the end where do you see yourself in five years' time?

[TD] One thing life has taught me is that almost all our fantasies are wrong - whether positive or negative. And that it's harder to function with expectations. I'm at the stage where I try not to build them up or rather shy away from them so that I don't experience further disappointments. But I think that everything is possible and everything is impossible at the same time. I find in myself a strong desire to express myself as an artist, but I have been rejecting the existing possibilities for several years now - because they damage my health to a great extent. So I'm at the point of wondering what's next, what's still possible, what can be salvaged from this. I've thought about some kind of commercialisation of some of the technology, but you have to invest a lot of money and a lot of work in that and you have to make it a pure business.... It's a moment of exploration. I think anything is possible.

[NP] I would like it to have some sort of happy ending but I understand it's some sort of coming to terms with what happened.

I was at that workshop with you guys and afterwards I felt I had touched something amazing. It opened my eyes and showed me a completely different perspective of creating. I want to say that what you create is really cool and I deeply believe in what you do.

[TD] I think the hope of the avant-garde is in young people. Because you have to have that very young, innocent hope in you - in a positive sense - the ability to push reality away for a while so that it doesn't get in the way. You have to do this to give yourself a moment of creative freedom, because you can only create the avant-garde in a sense of freedom and security. And you have to dedicate your whole life to it. Really your whole life. Oh, you also have to have a lot of physical strength, be healthy and drink a lot of water.

[NP] Well, I wish it all works out!

[TD] You have your positive ending.

[NP] I do! Thank you.

[TD] Thank you.