A few words about art school education and intimacy in the acting profession

How do you ensure an actor's safety on set or in the theatre when performing intimate scenes? Is the system of educating young students changing after reports of abuse in drama schools? What does the process look like? What should we know about working on intimate scenes? In a conversation with Natalia Podyma [NP], actress and author of Intimacy in the Acting Profession, Adrianna Malecka [AM], answers these and other questions.

The old drama school training system very often resembled a training ground for emotional survival. Fuchsia and other school 'traditions' taught acting students dedication from their earliest days, a willingness to play anything, anytime and anywhere. For some people it was the best time of their lives, for others it was memories they don't even want to return to. Once 'adult life' and playing more difficult scenes (including scenes requiring nudity) came after school, it was very common to cross boundaries in unhealthy ways. Nowadays, the actor's comfort on set is increasingly taken care of. A new specialisation has emerged - intimacy coordinator.

[NP] I read your MA on the recommendation of a colleague and thank you so much for writing it! Often these topics are swept under the carpet. How did you come up with the idea to publish about intimacy in the acting profession?

[AM] After my fourth year at university, I had a workshop on intimacy coordination organised by the Theatre Academy in Warsaw as part of the "Change now!”. It was the first workshop of its kind with Vanessa Coffey, a British IC, for the girls taking part in the play The Club.

When we met in front of the computer screens and started talking, I realised how many things I was already dealing with somewhere. In Poland, the tools Vanessa was talking about are not yet widely known, but abroad the topic of intimacy coordination is very present, it's starting to become common knowledge, not just a fashion or a legal safeguard. That's when I decided that this was a very good topic for a master's thesis. I immediately called Agata Adamicka, who is a lecturer at AT and was at the workshop with us, to be my supervisor. Agata agreed. But my work also came about because a month before the workshop I was taking part in the film Te Cholerne Peonie. And that's where I had a lot of intimate scenes that imprinted on me more strongly than they should have.

[NP] Theere was a lot of abuse?

[AM] No, there was no abuse. There, everyone wanted to do well, but there were so many things going on... we didn't know how to do it, no one had the knowledge or tools on how to protect me from the negative consequences of playing such scenes. At that time there weren't many intimacy coordinators, besides, it was a student etude whose budget wouldn't have allowed for hiring one anyway. Meanwhile, while working on set, the problems got worse, so that by the last day of shooting I was already struggling with my emotions and not with the role I had to create. This, in turn, introduced me to the feeling that I was working unprofessionally, which plunged me further into these thoughts.

Fortunately, the experienced cameraman present on set noticed that I was feeling unwell privately - it was evident on camera. So he gave me time, more space and... somehow it went, I managed to do it. But I still remember reliving it for a very long time, until that memorable workshop, where we were given a practical task for a given part of the scene and we were supposed to think of as many questions as we could ask. In the process of asking more questions, I realised that I should have asked them on set, a month before.

[NP] You mentioned the show The Club. I had the opportunity to watch it. It touches on a very important and powerful subject. Why was this play created? Were you a group of girls who spoke about this topic because they had experienced abuse from the school? Or did you just want to draw attention to it because the topic was important to you and that's why you decided to do it?

[AM] It was a suggestion from my year mates, who noticed that we girls had very small roles in graduations and started to fear for our future. They said it would be good to do one extra project. We started talking to the Student Ombudsman - Agata Adamiecka - about it. We created a diagnosis that made it clear that we had been discriminated against on a gender basis during school and that something like this happens everywhere where male discourse dominates, and this was the case in theatre until recently. I'm not accusing anyone here of course, no one wanted to discriminate against us consciously. It's simply a matter of years worked by educators in a particular theatre system that is very patriarchal. We also noticed that not once have we worked on a text by a woman, written by a woman, and that among our directors there are only men. In opposition to this state of affairs, our project was born. We managed to get funding from the "Change Now!" programme, and we chose Veronika Szczawinska as the director. It was she who was cast by the actresses for the role of director, not the other way around. She brought us three texts as proposals, but we accepted the Club unanimously. It was an insanely heavy piece, filled with incredible stories of women. At the very beginning I was afraid of it, probably the most of all my colleagues, because in the proposed narrative I saw the danger that the audience would perceive what we were talking about in the play as our stories. Originally, according to the script, the action takes place in Sweden and we emphasised this a lot in the performance. But even so, somewhere in those layers it was apparent that the problems described in the book are just as much about Polish culture and what is happening in Poland. During the conversations and rehearsals, a lot of situations came to the surface that were difficult for us. That's probably why this text was so 'let through' by us that it became one of the more important plays of that season. And paradoxically, although I was the one who was most afraid of it being 'not about us', I ended up doing a theatre stand-up as part of the performance, in which I say what my name is and talk about Poland, not Sweden. But it was a safe enough group that we could afford to make such gestures.

[NP] You've said that working on set, you weren't aware of how many questions you could ask. Is there a subject at the Theatre Academy where you learn to deal with nudity and intimacy? Is it covered at all in the programme?

[AM] It is changing. In my day, there was no such thing, so both my yearbook and the other people who graduated earlier than me didn't have that experience in school and everything that happened in that field in their career happened for the first time on set. I mean, if any of us had an intimate scene like that, that's where we learned really. However, I was very fortunate to still catch that workshop.

As far as I know, there are now workshops for students and this has been introduced. Each student gets tools that they can work with on set.

[NP] Did you experience any abuse from educators? Did you hear words of support while getting used to the intimacy? However, were the comments and remarks more 'figurative'? What experiences have you had?

[AM] Difficult... In my master's thesis, I describe a moment from working on an exam at Halina and Jan Machulski's private Acting School - "it was Arthur Miller's The Witches of Salem. The lecturer suggested one day that it would probably be a good idea for me to strip down and throw on my partner without a nightie (in just my panties) and start kissing him passionately. As I had seen a Danzig interpretation of this drama in which an actress undressed in the same scene, I said that I understood the premise and concept, and that it was probably indeed possible to do it that way. For the next few days of rehearsals I didn't do it, we didn't talk about how to prepare for it, and while we were working on this scene the lecturer suggested (in jest) that my scene partner and I should sleep with each other. We never rehearsed the moment of undress, even if only alone with my colleague and the lecturer (there were twelve students in this exam and they were all on stage the whole time). Finally, the day of the reception came and the lecturer said: "Well, you're undressing, aren't you?". On the same day she came up with another idea for intimate content involving me - during the prologue I was to masturbate while lying on the floor near the front row of the audience. The conversation was short and went roughly like this: "And you, Ada, will you masturbate", "Masturbate?", I replied with undisguised reluctance. "Don't you want to? It's Dorota who will definitely do it. Right Dorota? And you will then have sex with Nicholas at the ladder". So I had a choice. Either a scene of individual masturbation or a scene of intercourse in a standing position with a colleague who played the character of a priest. I agreed to the former. Acting individually seemed somehow safer, and I felt I was too ambitious to say no completely. It's also possible that fear and my defence system of pleasing all the lecturers, which kicked in during a selection year at the Lodz Film School, was still at work. I was not given instructions on how to perform a scene. As I mentioned, these assignments were offered on the day of the exam, a few hours before it started. So I approached them strongly intuitively." 1 This was probably one of those hardest examples for me, the worst anyway.

[NP] Who did you write your master's thesis for? Who may find this publication most valuable? Only for young people?

[AM] I mainly wrote it to finish school and defend my MA, but I knew that if I was already doing something, I wanted to do it well and interestingly. I'm glad I chose this topic, although it came out quite spontaneously. I had other topic suggestions beforehand. My first idea was a topic about the impact of selection on the subsequent fate of an actor's career. I wanted to write about being kicked out of school from different perspectives, not just negative ones. However, I found that this topic is no longer relevant because selection as such has been phased out, at least from the Theatre Academy. I know it is starting to be phased out from other schools.

I wrote my MA for myself in order to better understand what happened on the film set. I wanted to name the phenomenon, out of a sense of respect for the people I was working with. I believe that none of these things were their fault.

I think at this point my thesis is for actors and actresses,male and female students, but also directors and directors or choreographers and choreographers who want to work on such a subject themselves. I have managed to do something that is the first publication on this subject from the perspective of an actress - the first and only one in the world. In the near future, the publication will also be translated into English.

[NP] Will your publication be distributed more widely? Do you have any contact with the publishing house?

[AM] She is available all the time on the Theatre Academy website. It's free of charge. Once it's translated, it will probably be on the websites of the partner schools involved in the "CHANGE NOW !" project.

[NP] Do you think differently about intimacy in retrospect?

[AM] Hmm... I have already done two etudes as intimacy coordinator. I don't consider myself fully qualified in this subject and by virtue of my lack of certification I don't call myself an intimacy coordinator, but this is the role and function I've performed on two student sets, as part of student support. I know that in such productions no one can financially afford a real coordinator/coordinator.

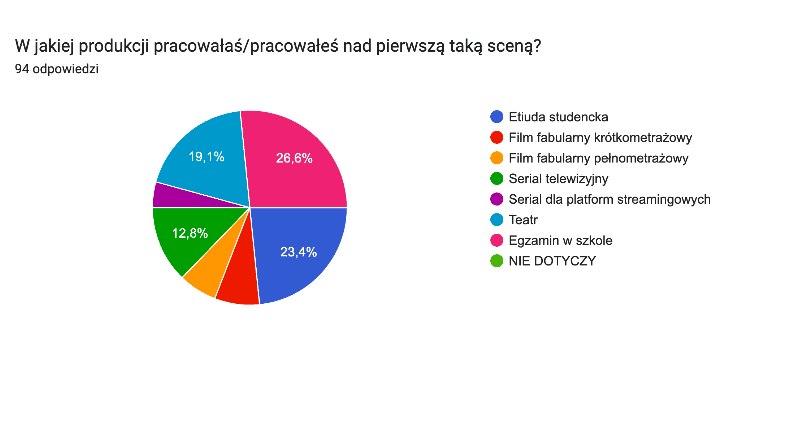

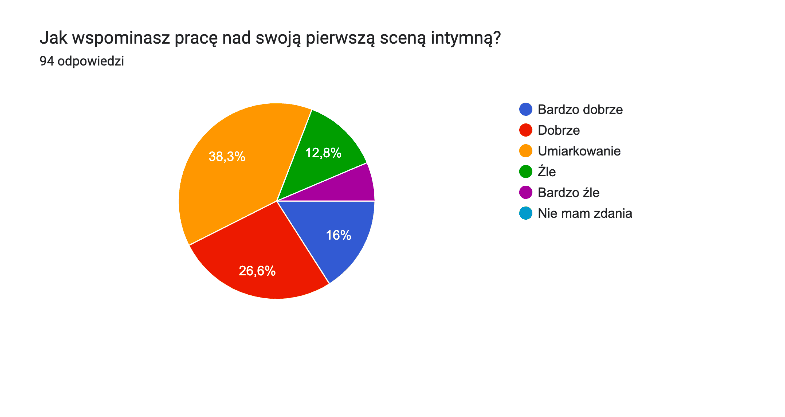

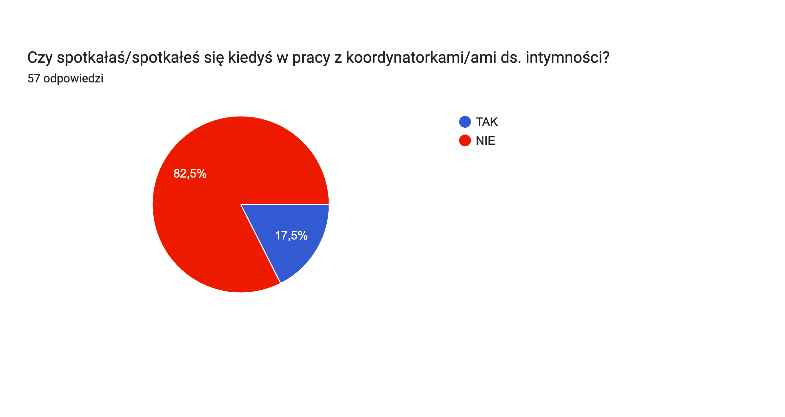

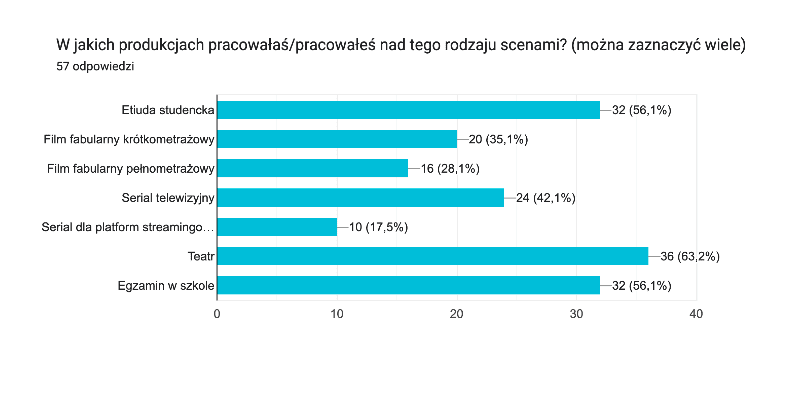

In preparation for speaking at an international conference on intimacy coordination, I conducted research on the availability of coordination and the results were not at all surprising. I surveyed over a hundred people, asking if they had been in contact with intimacy scenes, if it was comfortable for them, if they worked with a coordinator.

I'm very keen to expand the knowledge that actors mostly start their contact with intimacy in the profession with student shorts and low-budget films.

Only a few actors, manage to get a job right away at Netflix, HBO or other big production groups with an intimacy coordinator on board. This practice is starting to get bolder and bolder, but further down the line, these are just some producers. The rest, the people who may only be working with Netflix in 20 years' time, are just now starting on student sets. And that's where you need the most knowledge and the most support. I was one of those people as were many of my colleagues. What I care most about is remembering all those people and that's who I want to speak to.

[NP] What did you learn in your work on intimacy coordination?

[AM] I have learnt about language and communication. In my opinion, I speak to people completely differently now. I perceive how people speak to each other differently. Just because something is obvious to me, doesn't mean it is for the other person too. It's very easy to hurt someone with words or just to make them feel uncomfortable. This is probably the most important lesson I have learnt in the last few years. You can communicate things differently! I was really under the impression that the way I think - everyone thinks. It turns out that someone may have a completely different mode of thinking and what is obvious to me - to someone else may be completely unintuitive. So conversation is key when dealing with more difficult scenes, intimate and otherwise.

[NP] And on the sets or in the theatre in Sosnowiec where you play, do you see any difference between how you communicate and how older people with more experience do it? Are the boundaries between the old and new generation of actors blurring? But is there a communication gap?

[AM] There is, but it's getting smaller and smaller. These are people who just have a hard time because they don't fully understand the new language. Now that I see this clash of generations, being an assistant at the Theatre Academy, I have the chance to talk and communicate in both fields. And it is certainly interesting. It's like that in theatre too. At our Zagłębie Theatre in Sosnowiec, we are lucky to come across creative teams who know the language of good feedback, who know how to communicate with actors, with technical people and other theatre workers.

Now we are working with Justyna Sobczyk, who is also great at communicating at work; she is a post-graduate in pedagogy and teaches theatre pedagogy. Through this collaboration I can see that people are opening up and for me the month of rehearsals with Justyna was also very crucial... But I know that these tools are not yet present everywhere.

[NP] The artistic community welcomes change?

[AM] Rather reluctantly. It's still to be seen, it's still to be heard and it's still going to take some time. But it's getting better and that too needs to be communicated strongly. I remember well the beginnings of these changes. I was at a school in Lodz after my high school graduation and I was kicked out of the school for lack of progression. For me, this is just an example of how problems used to be solved. Mostly, first of all, we threaten, and to make sure the threats are covered, we will expel a few people now and then. Then there's the fuchsia, which I myself went through twice - in Lodz and in Warsaw. The fuchsia from the beginning taught hierarchy and how to act in our environment. There was no question of this environment changing - it was you who had to submit to the environment. And being in Łódź, I accepted this, believing that I had caught God by the feet - after all, there were 1,500 applicants, and I was the one who got into the school, and right after graduation. I accepted these rules as humbly as I could and, to be honest, I feel that the fluke killed a lot of things in me. That was obviously rebuilt many years later, after I left school, after I started studying in Warsaw, where I felt much better, etc. But through that, I also kept a very close eye on drama schools and today you can see that the change is huge. In my opinion, the biggest one has happened in Warsaw. This is thanks to Agata Adamiecka, Wojciech Malajkat, the school's chancellor and many other people. In the first year, by the way, I myself was against these changes. At the time I thought: , "This is killing our beautiful environment, our traditions and culture developed over many years". Now I think that not having a fuchsia can even save someone's life, steer them away from alcoholism and depression.

Speech by Adrianna Malecka on: "Intimacy in the actor's work at the stage of entering the profession. The practical perspective"

[NP] I have the impression that the profession of intimacy coordinator has suddenly arisen. Is it common to see co-ordinators working with theatres?

[AM] I think it will only be a few years before we can say that the coordinator has entered the theatre. We have very few coordinators in Poland - ¾ are people who have completed special international courses. This is a fresh profession. But in fact, there are more or less 12 to 16 people working in this profession - quite often they are people who don't have such courses, but have, for example, a background in choreography, psychology, sexology, acting and directing.

[NP] At what level can an intimacy coordinator help with scenes?

[AM] "Many intimacy coordinators work on the so-called 5C system (5C Key), which consists of the following elements: context, communication, consent, choreography, closure/check-in-closure." - I have described it in detail in the master thesis.

In fact, the coordinator has a lot of functions within it. The most important function of coordinators is to make all parties feel comfortable and safe. It is kind of like a mediator between the parties - a person who can talk to the acting team, the directing team, the production team and so on in a calm and private way. He's like a psychologist, just helping to name emotions and pose questions. And that makes communication easier when shooting intimate scenes. He's also the person who looks at what the conditions are on set and makes sure that the set is definitely closed. It needs to be safe. During the filming of intimate scenes, only those people are present who need to be, i.e. the soundman, the cameraman, someone at the preview, the director, the sharpener - 10 other people are not needed there.

The coordinator also talks about the actors' private boundaries, helps them locate and name them. He carries out exercises to help break down these boundaries slowly, in a safe and hygienic way. Recently I had a situation where the actors didn't know each other, but it was clear that they were going to kiss, touch and hug. First they had to get to know each other, help them get to know their bodies and get two strangers used to physical contact. This kind of exercise* means that slowly, gradually, we will know our touch, we will know what our limits are, where we don't touch, where we touch. We will answer different questions, what hurts someone, how they feel, we will call ourselves a 'safety word', which is also very important. Very different things happen on set and in theatre. In fact, it's so mind blowing.

It's also very important to write down a contract - nudity riders - the kind of documents that describe everything, including the number of doubles dedicated to that particular take. For example: "I, as an actress, allow you to have my breasts on four dubs, but I beg you to buckle down and let's do it on four dubs, because I wouldn't want to do a fifth anymore". Obviously there are some people who don't have a problem with this, but on the other hand you also have to think about the comfort of those watching. In fact, it is not only the person who undresses who is the performer of the intimate content. You have to take care of the whole team, e.g. tell the editor/editor that there are scenes with nudity. Imagine an editor who doesn't know what an etude is and fires it off in front of her friends. Suddenly 10 strangers see it. All material should be labelled that it's nudity - it's all written in such a protocol.

The coordinator/co-ordinator takes some of the responsibility away from each party, making the plan more structured and there is less risk of chaos. When we're working on a fight scene, we hire a stuntman so no one gets hurt physically, the same way we hire an intimacy coordinator so no one gets hurt mentally.

[NP] And how it looks like in practice? How much time does the coordinator need to prepare? To work with the actors? What does that line of communication look like?

[AM] On sets, time is always limited. Time is money - a lot of money. So... rehearsals and work before the set are the most important. The whole system of work of the coordinators is divided into sections.

Before shooting is the most work (at least in my experience), because the coordinator has to gather all the information about the scenes. She has to read the script, find out how much intimate content there is, describe it, meet with the director, the cinematographer, understand why the nudity is needed and how many takes there are for it, find out what their ideas are for the realisation - what the choreography should look like, what they care most about in the scene, what emotions they expect....

Only after discussions with the director, the cinematographer and the production does the stage of arrangements with the actors begin. More often than not, the starting point is a conversation about what they know about the film/etude and the intimate scenes in the script, what they would like to ask, what their boundaries are, what their 'safety word' is, whether they have any body limitations, whether they agree to all the scenes proposed. If they agree, well then it goes into detail, e.g. do they agree with the number of takes, how many doubles in this take, etc.?

Then there are rehearsals. They should take place in the same set where you are shooting, but this rarely happens. Rather, there is no time or money for that. In that case, the production should provide a neutral location. Ideally, it should be some kind of room to help determine what it will look like later.

In my opinion there should be a minimum of two rehearsals. The first rehearsal should be simply 'talking' and the second should be choreographed with the cinematographer. And in clothes, of course. The same rehearsal should be done on set, already in the scenery. That is, even if we've already had a conversation and so on, we still need to do a rehearsal first, to find out exactly how it's going to look before we get undressed.

And only then, when readiness is announced on the set, do we get the people unnecessary for the shot out, and when the shot is ready, we just finish the work. An important stage is also to contact the actor/actress a few days after the set. This is very important because a secondary reaction can occur. Because of the adrenaline during the scene, you may not pay any attention at all to what you are doing, but after a few days you may get some strange emotions, feelings that you have done something against yourself. And that's when the coordinator is needed for that kind of conversation, for that kind of end to the process. After the set of the film I describe in my MA, my director did something like that, completely unconsciously using IC tools. She met with me three days after the set. That's when I told her that the most difficult scene for me was the last scene. There was less and less time for it because of the delays. Time was chasing us and I was stressed because I had a block. The coordinator also agrees with the production managers that such scenes should be in the first part of the day. This ensures that the actors are more comfortable by being sure that even if one does get delayed, these scenes will not be 'chased'. On that fateful day when we were shooting the last scenes of the film, the biggest blow for me was when we had the last 15-20 minutes of our work allocated to the nudity scene. It's a situation where you have to act, no matter that you don't feel like it. You're doing a scene, but you don't know if you're doing it right because all you're thinking about is standing there naked. And suddenly you realise that 15 people are standing in front of the preview watching it, you don't want to do another one, and it's only the first take. And then there's the delay and the desire to be professional.

[NP] What exercises do you recommend actors do when the intimacy coordinator is missing on set and they have to take matters into their own hands?

[AM] There is one that I do quite often and recommend, particularly when the scene is quite close. It involves calling your boundaries. Two people who are going to perform intimate content are facing each other. Person A takes person B's hand and they decide where person B can touch them. Then questions arise, person A also asks person B, e.g. "Is it ok for you to touch/touch my breasts?". It is important that this attention is mutual. Because both the person touching and the person being touched can feel discomfort.

Another part of this exercise is to talk about where we noticed that this barrier was higher or lower. And together we try to blur those boundaries.

[NP] How do you think this "Change Now!" transition can be accelerated? Can it be accelerated somehow? Does it just have to flow?

[AM] We are at a moment of change, but it's an evolution rather than a revolution. If we accelerate and push, we will meet more resistance. The younger generation, who are starting to be much more aware, already know much better what they can and cannot do - this is a contributor to this change becoming bigger and bigger. I can understand 'boning up' for the sake of art. I think it's worth it sometimes, but the more secure conditions you have, the more enjoyable it is. I see this hope for change, for conversation. I want to believe that the people who choose this profession now know that this is a profession, not a mission. We don't treat people, it's supposed to be entertainment for us too. This is something I have carried in my head for a long time - do we live to work or work to live and in this profession you need that balance.